When Blackstone Infrastructure completed its $5.65 billion acquisition of Safe Harbor Marinas on 30 April 2025, the transaction turned more than a few heads. As the largest marina deal in history, it highlighted a fundamental shift: marinas, once regarded as small-scale, fragmented local businesses, are now attracting serious attention from institutional investors.

Yet while the Blackstone–Safe Harbor deal garnered widespread attention, institutional capital had already been entering the marina sector for more than a decade. Safe Harbor itself was founded in 2015 with backing from private equity firms including American Infrastructure Funds, Guggenheim Partners and Koch Real Estate Investments. Its roll-up strategy was among the first to apply scalable, investment-led models to marinas. Suntex Marinas pursued a similar approach. In 2021 it was recapitalised by Centerbridge Partners and Resilient Capital Partners.

Although the United States has seen the most extensive institutional marina activity to date, capital is also flowing into marina markets across Europe and the Pacific. This raises a broader question: what exactly is attracting institutional capital to marinas? And what does this growing involvement mean for the future of the sector?

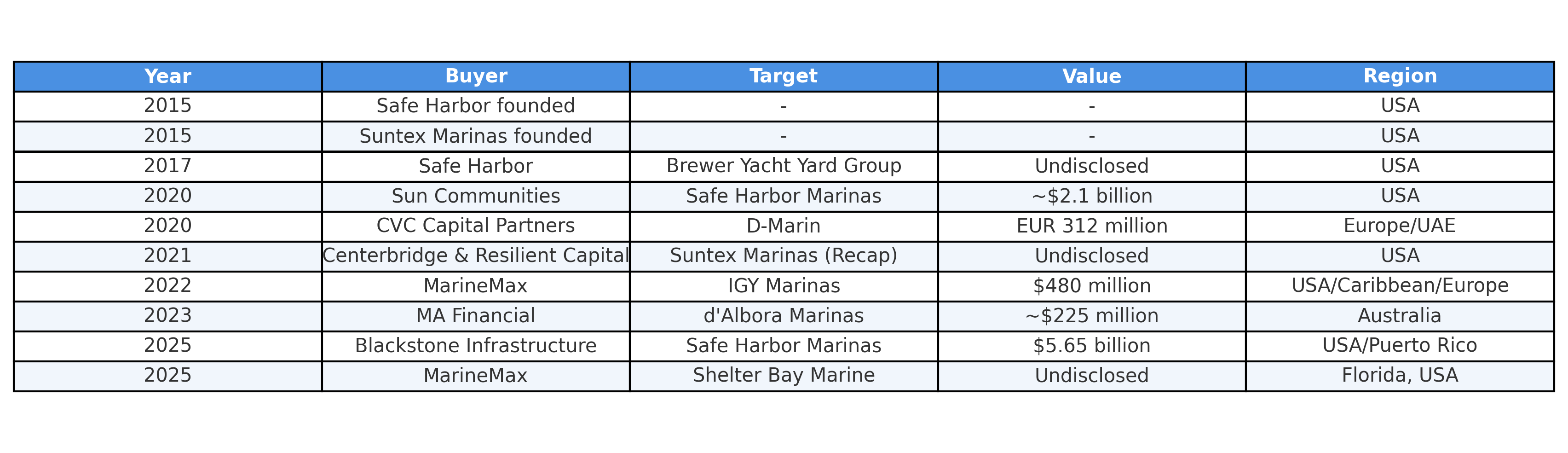

The table below highlights recent transactions involving institutional investors and key stakeholders in the marina sector, illustrating the global rise of institutional involvement.

The evolution of marinas: from parking spaces to complex platforms

Historically, marinas were fragmented and often owned by small, family-run operators. They were conceived primarily as static, functional infrastructure, designed to provide mooring rather than generate long-term operational value.

Paolo Bianchi, President of White Milestone, marina planners and certified valuers, attributes this to the original development model: “In countries like Italy, marinas were typically built by large contractors or residential developers with the sole aim of selling berths and walking away, leaving behind a basic parking space for boats. Operational complexity was low, and returns were often front-loaded rather than recurring. That short-term planning model led to counterproductive outcomes, the effects of which are still being addressed today.”

While there were some early examples of consolidation and operational expansion, MDL Marinas in the UK has operated a chain of sites since the mid-1970s, and d’Albora had established a network prior to its acquisition by MA Financial.

Marinas have since evolved and now operate at varying levels of complexity. As Bianchi explains: “Marinas serve as the interface between the offerings of sea and land. They act as catalysts that require substantial investment, often resulting in permanent changes to the coastline and a significant impact on the local economy. At one end of the spectrum are marinas that provide only essential services, such as basic assistance and a café. This model has since expanded. Today, waterfront developments and mixed-use complexes offer a broader range of services and multiple sources of revenue, including robust technical support, fuel provision and appealing food, beverage and hospitality options.”

He continues: “A modern marina must be professionally and consistently operated over the long term to generate a sustainable economic return. Marinas are no longer developed simply to sell berths on paper. They tend to be significantly more profitable when moorings are managed on seasonal or annual terms, as part of a broader service offering.”

Baxter Underwood, CEO of Safe Harbor Marinas, links this growing complexity to the evolving demands of boaters and the benefits of scale. “One reason for some level of consolidation in marinas, is the realisation that networks of marinas benefit boaters more than single locations,” he said. “Demands of boaters have evolved, and we believe scaled networks of marinas are better positioned to provide customers the one-stop shop experience, additional amenities and community they desire.”

Ekrem Reyhancıoğlu, Managing Director of Poralu Marine, part of the Wearth Group, reinforces this point, noting that as boating demand has grown — particularly among middle-class owners and in the superyacht segment — marinas have had to adapt and diversify. “It’s no longer just a place to park boats; marinas are increasingly seen as business ecosystems capable of generating broader value.” He explains that the presence of large superyachts not only brings direct income but also attracts ancillary businesses and raises the overall investment appeal of the surrounding area.

Despite increasing complexity and early signs of consolidation, much of the marina sector remains fragmented. István Szőke, Managing Partner at CVC Capital Partners, which acquired D-Marin in 2020, observed: “In the big scheme of things, the marina sector is still largely a fragmented industry.”

This lingering fragmentation combined with rising customer expectations and growing operational demands is part of what makes the sector increasingly attractive to institutional investors.

What is attracting institutional capital to marinas?

Institutional capital’s growing interest in the marina sector can be attributed to its evolving character. No longer seen solely as berthing facilities, marinas are increasingly recognised as complex, multi-revenue platforms incorporating hospitality, retail, and refit services.

Underwood (Safe Harbor Marinas) emphasises that this operational evolution has raised the bar for customer expectations and that meeting these expectations requires substantial investment. “Our growth has always required access to capital,” he notes. “Whether we are investing to replace ageing infrastructure or to enhance the offerings at our existing locations, we know that a strong and vision-aligned capital partner is critical.”

From the investor side, Heidi Boyd, Senior Managing Director of Blackstone Infrastructure, points to long-term sectoral trends and rising infrastructure demands as key attractions. “Institutional investors are interested in this asset class because it has strong long-term tailwinds and because considerable capital is required to meet the needs of customers, which include investment into docks, uplands amenities and related infrastructure,” she said. “Like any leisure activity, the needs of the customer will continue to evolve and marinas will need capital to adapt to provide the right frictionless experience to boaters, captains and other customers.”

Bryan Redmond, CEO of Suntex Marinas offers a similar view, noting that the sector’s maturing fundamentals have brought it more clearly into focus for institutional capital. “The marina sector has become more attractive due to a limited supply of waterfront assets and strong consumer demand for recreational boating,” he states. “As the industry matures, it has presented an opportunity for consolidation and operational efficiencies, aligning well with institutional investment criteria.”

Redmond further adds that its recapitalisation with Centerbridge Partners and Resilient Capital Partners has enabled long-term planning and infrastructure investment, while supporting scaled growth and enhanced customer experience.

When discussing CVC’s 2020 acquisition of D-Marin from Dogus Group, Szőke explained that the decision was not driven by a sector-specific mandate, but by the opportunity to transform an underdeveloped business with clear potential for consolidation and professionalisation, particularly outside the United States. “We look for good businesses we can make great,” the executive said. “When we studied the marina sector, it became clear there was strong potential, especially through investment in digital infrastructure, customer experience and multi-site operations. These are areas typically out of reach for smaller, family-run operators.”

MA Financial’s entry into the marina sector reflects a distinct approach. Rather than viewing marinas solely as infrastructure assets, MA Financial treats them as real estate alternatives with embedded operational upside. “We are attracted to real estate alternatives where we have greater control and influence over asset-level returns,” the firm explained. “This approach allows us to maximise both the value of the underlying real estate and the performance of the operating business.”

Since acquiring the d’Albora portfolio, MA Financial has recorded strong organic growth, completed several complementary acquisitions, and reactivated a previously underutilised development pipeline. With high occupancy levels and Australia’s only corporatised marina management platform, MA Financial sees d’Albora as a model for what is possible when institutional discipline meets a traditionally fragmented asset class.

Together, these perspectives reflect a sector in transition, one that appeals to institutional investors not only because marinas have become more sophisticated and service-driven, but also because, particularly in Europe, the sector remains undercapitalised and ripe for long-term value creation through professionalisation, consolidation and reinvestment.

A growing global trend with local limits

As the marina sector becomes more consolidated and attracts rising levels of institutional capital globally, the pace and scale of mergers and acquisitions often depend on local regulatory frameworks and ownership structures. This dynamic is particularly evident when comparing markets such as the United States and Europe.

Szőke acknowledges that while there are opportunities for consolidation in Europe, structural limitations persist. By contrast, the outlook is more favourable in the United States, where a greater proportion of marinas are privately owned. “The U.S. model is very different,” he says. “It is primarily based on freehold ownership, whereas in Europe, even among smaller operators, marinas tend to operate under concession-based agreements.”

Bianchi echoes this view, describing the lack of freehold ownership as a key obstacle to the consolidation of certain types of berthing infrastructure. “In Italy, there is a negligible percentage of freehold ownership. A marina built on private land is very uncommon, as access to the sea typically depends on state-owned coastal property. Despite the often limited duration of state concessions, this mechanism has nonetheless proven effective in encouraging developers, investors and operators to make the most of the designated areas, often resulting in outstanding contributions to the local social and economic fabric.”

He also highlights the complexity of the Mediterranean market. “The Med is a different case. It primarily serves larger yachts and is almost entirely coastal, with strong involvement from local authorities. The level of complexity is much higher. In the U.S., many marinas can be categorised in similar ways, but in the Med, every location is different. The services, the infrastructure, the surrounding areas – all of it varies significantly.”

Looking further east, Ekrem Reyhancıoğlu, Managing Director of Poralu Marine, offers a different perspective, noting that the marina market in Asia remains less mature than in Europe and significantly behind the United States. “I think most marinas that would be attractive for acquisition still need to be able to serve superyachts,” he says. “That requires superyacht-ready infrastructure and services that meet international marina standards. Apart from one or two examples, the majority of marinas in the region are already full but lack the premium amenities required. Pontoon conditions are often poor, upland facilities are limited, and many layouts are outdated. Even those considered among the best are now 15 years old and beginning to show their age.”

Nevertheless, he remains optimistic about the region’s potential. “Asia adapts very quickly,” he added. “In 10 years, I hope we’ll see more growth, more marinas, and perhaps the major marina operators and development companies will expand into the region. But there is still work to be done.”

These regional disparities underscore that while institutional interest in marinas is accelerating worldwide, the path to consolidation and expansion is far from uniform. Freehold ownership, regulatory clarity and infrastructure quality remain key enablers or obstacles depending on the region. As the sector continues to evolve, investment strategies will need to be tailored not only to global trends but also to the structural nuances of each region.

What’s next for marina investments?

Looking ahead, the marina sector appears poised for continued transformation. Underwood predicts further transition from individual to institutional ownership. “We would expect the continued rollover of marina ownership from individual ownership to institutional ownership to address opportunities,” he says. “This should be a net-positive for the boating industry given that there is considerable scarcity of large-scale, high-quality marinas and shipyards to serve the superyacht fleet.”

Redmond agrees that consolidation will remain a defining trend, though its pace will depend on market conditions. “Consolidation will continue, but the pace will depend on interest rates, market conditions and available inventory,” the company states. “As the industry evolves, we will also see increased focus on value creation through operational improvements rather than just expansion.”

Bianchi adds another dimension, noting that interest is also growing among a broader range of commercial players beyond financial investors. “Boatyards, fuel providers, cruise lines and maritime agencies are increasingly viewing marinas as strategic assets,” he says, adding that many of these companies already possess the scale, organisational structures and market presence to operate modern tourist ports effectively.

“Even within today’s more diverse landscape, specialised operators with centralised structures and proven capabilities remain well-positioned to acquire, manage and integrate marinas into broader commercial and operational platforms. Marinas are hubs where multiple activities converge, and their potential is almost limitless when guided by strategic business planning. The key lies in defining the most suitable mix of services and products to offer, framed within a carefully calculated economic and financial model – a language that many investors, including institutional ones, fully understand,” he affirms.

It would appear that the era of marinas being owned and operated solely by traditional players has passed. As the sector becomes more consolidated and increasingly attractive for acquisitions, a broader range of stakeholders are now shaping its next chapter.

Over the next decade, targeted infrastructure upgrades and increased professionalisation are expected to unlock new investment corridors and accelerate the sector’s evolution into a fully integrated, institutional-grade asset class.

.avif)